Nun dengah! My name is Bethany Luhong Balan, but you can call me Bee.

I'm a freelance multimedia designer, poet, and self-taught visual artist from Kuching, Sarawak. I have a bachelor degree in graphic design and I've been involved in creative ventures in one way or another for as long as I can remember; I've participated in various spoken word performances, contributed to poetry anthologies and art exhibitions, and even took part in a virtual artist residency.As a multi-disciplinary artist, I approach my work in a playful and subversive way, invoking a sense of magic realism to each piece, whether the medium is embroidery, poetry, clay, or digital art.

<< back to Gallery

This piece explores the future of humanity and how it relates to the environment. As a Kayan person, I believe that the natural world is inseparable from culture, so in a conversation about climate change, we have to speak about Indigenous heritage as well. We are losing Indigenous knowledge, we are losing recipes for environmental stewardship. The empty, upended ingen—the Kayan word for a big woven basket used to carry produce back from the farm—with brittle bones and crude imitations of bounty spilling out of it was how I captured this anxiety about the future of humanity. The embroidery thread, which I dyed with onion skin, roselle flowers, and coffee, will eventually fade. The little jars of dirt anchoring the tapestry on the left and right: Santubong to the West, Sungai Asap to the East. Unglazed beads from Lawas, raw and incomplete. Crude depictions of durian, engkabang, black pepper; almost as if the artist was trying to draw them based on second hand accounts instead of real life—each of these elements reflects the anxiety I have about the future. But perhaps there is a glimmer of hope. Nothing is truly dead until we stop talking about it or recreating it. So maybe this is me trying to create a future I would like to see. A future where indigenous knowledge and values are part of the conversation: honoured, vital, and alive.

<< back to Gallery

These two pieces were made to complement each other, hence their names: Tanah & Air. I’ve had this image of a tiger pelt in an oil palm plantation—a visual analogy to habitat loss and animal extinction due to deforestation—in my head for a long time, but I was unsure how to execute it. In the end I decided on this mixture of embroidery, appliqué, and assemblage, but using elements that we as Malaysians are more familiar with. The oil palm trees and leaves are made from cut out batik motifs, the oil palm cluster is represented by a kabo bead, a significant culture identifier for the Orang Ulu community. The contrast between the dark subject matter and the bright, almost innocent way it’s portrayed is something that I enjoyed playing with. It reflects that certain blithe ignorance we all face when speaking about the impacts of deforestation or pollution.Air was made using similar methods to Tanah, but with more recycled and repurposed materials: the fishing net is old fruit packaging, the catch of the day being various bits of debris and trash I’ve collected. The composition brings to mind illustrated children’s storybooks, which begs the question: in a hundred years from now, what kind of stories will we be telling our kids about the Earth, the environment, and our role in preserving—or destroying—it? Will these vignettes be our reality one day? Or will they remain cautionary tales?

<< back to Gallery(H)ARUS Series (2022)

When I think of menstruation, I think of pain, stigma, and shame. I think of how having your period is such an intrinsic part of being human but we can’t speak openly about it because it’s treated with so much disgust by people who don’t even experience it first hand. This series of works aim to confront that perception, to challenge myself and my audience to view menstruation as something essential, even precious; Arus yang Harus, a necessary flow. I chose embroidery as my medium for a number of reasons, one of which is its connotation to “women’s work”: i.e. a sphere of art that has historically been viewed as inferior, trivial, or frivolous compared to more “serious” male-dominated mediums. But mostly I chose this specific technique for how painstaking and tedious it is. With each stitch I gained an appreciation for the process as well as for my body. I wanted it to be a labour of love, a slow and steady unveiling: what was hidden is now seen, what was foreign is making itself familiar, and it is beautiful.

<< back to GalleryHudo' Series (2021 - 2022)

Hudo’ is the Kayan word for mask, worn by shamans during sacred rituals and ceremonies. These rituals were performed for many occasions and functions—to usher in a good harvest, to appease the spirits before a big event or battle with a warring tribe—and, most fascinating and topical of all, to scare away sickness. Mask as medicine, literally. Hudo’ I was created while we were all still adjusting to the “new norm” of the pandemic, and Hudo’ II was created a year after—the difference in my mental state and attitude while making each of these pieces is readily apparent. The connection of mask as medicine in the post-Covid world is the theme behind both, but they originate from two different perspectives. One, a feeling of claustrophobic powerlessness—bleached of colour, literally trapped, brought low from such a lofty, sacred position—while the other is more lighthearted and playful; a democratisation of mysticism, a reimagining of science as magic. Traditionally, hudo’ was a tool reserved exclusively for shamans (dayung), but now everyone wears a mask; essentially, everyone is their own dayung. Modernity has brought us increased literacy and decentralisation of data, and our old superstitions and belief systems have become obsolete. I was interested in what this intersection of spirituality and science would look like.

EVENT GRAPHIC

Word of Mouth:

BorNeon (2025)

ILLUSTRATION

Aram Bekelala (2024)

EVENT GRAPHIC

Word of Mouth: Kembali (2024)

EVENT GRAPHIC

Malaysian National Poetry Slam

Open Mic (2022)

EVENT GRAPHIC

Word of Mouth: Menua (2022)

EVENT GRAPHIC

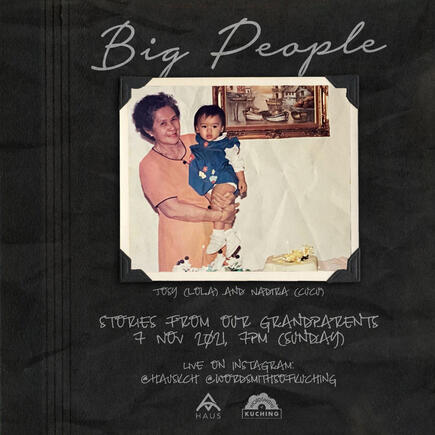

Big People/Kelunan Aya' (2021)

EVENT GRAPHIC

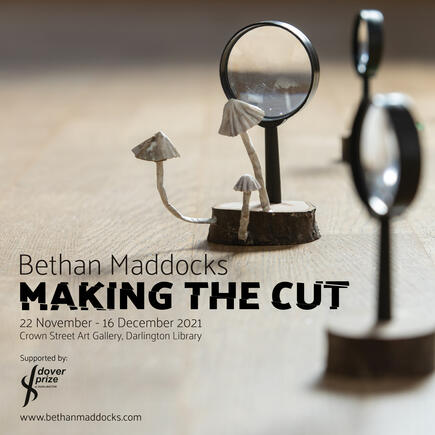

Making the Cut (2021)

EVENT GRAPHIC

Lingua Franca (2021)

Essay: On the Bakun Dam, and everything that drowned there

“Above a Drowned World, Existence is Resistance”Essay: On code-switching in poetry

“I have four tongues in my head, so please excuse me if I trip over my words”Poetry Anthology: On migration, borders, and how we can reimagine language into a tool for healing instead of violence

“To Dance Along The Wind”